It seems like a straightforward question. Strength is highly revered in sports, whether at the professional or hobbyist level. Ask any athlete about their priorities, and you’ll likely hear that strength training ranks near the top of the list. But like any worthwhile pursuit, the quest for “more strength” can make us naive—or greedy—with no clear endpoint in sight. If you’re the athlete who just hit a new deadlift max and tweaked your lower back (again), there’s a lot to unpack.

Framing strength training as an unquestioned good—something to always pursue more of—is an oversight. It comes with various costs for athletes across different sports, including chronic joint limitations, pain, performance plateaus, and movement restrictions, to name a few.

Which begs the question: How much strength do you really need for your sport? And for those chasing strength without a specific sport in mind, the question is just as important.

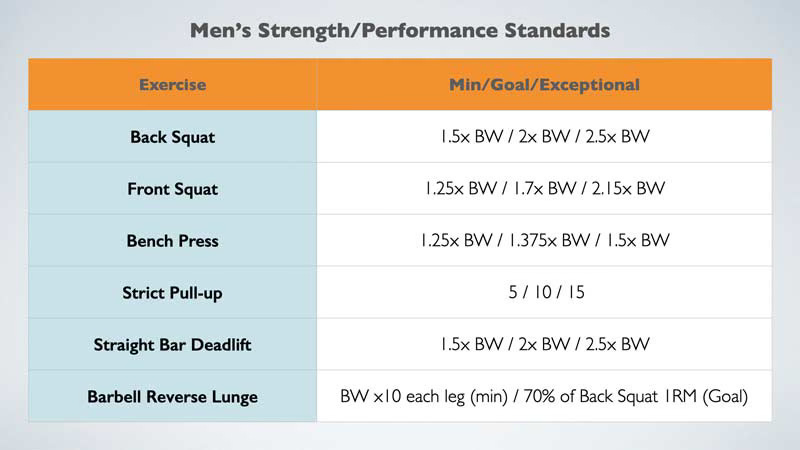

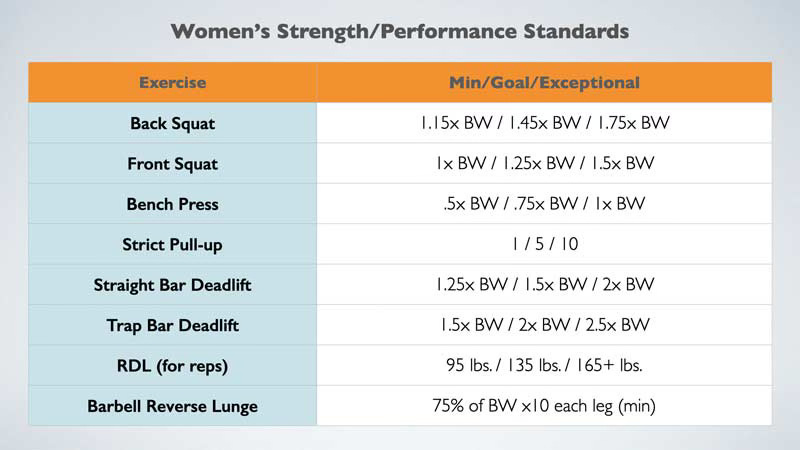

It is not uncommon to hear athletes adhering to standards approximating x2-2.5 times bodyweight for lifts like the squat and deadlift, with bench pressing goals being 1.25-1.5 times bodyweight. If you’ve spent any time in any strength training community, you’ve no doubt seen this chart or heard of a similar version:

(image source - https://simplifaster.com/articles/applying-relative-strength-standards/)

What is interesting about commonly accepted standards like these, is that they are notoriously evasive when it comes to pinning down their origins. As I tried to explore their roots, a few concerning points arose. The first, is that the thought process is largely driven from powerlifting community standards. Even books and articles that somewhat refer to these benchmarks are not precise about these numbers. Starting Strength by Mark Rippetoe, The Strength Athlete, and Powerlifting Basics informally mention these standards at best. Another author and elite powerlifter, Jim Wendler, makes references to these standards along with surpassing them. Then there is the legendary innovator and pioneer, Louie Simmons and the conjugate method. This approach was all about getting his athletes freakishly strong. His athletes repeatedly broke world records and created a legitimate legacy with their esteemed approach, influencing generations of athletes and lifters.

Strength for athletes who are not powerlifters

A common theme seen here is, powerlifting coaches have some phenomenal wisdom for how to get powerlifting athletes as strong as possible for their specific sport. However, taking nothing away from these sport specific standards, these have become somewhat adhered to empirically and anecdotally across many other sports. There are a number of problems with both the volume required to hit such feats of strength, as there are with the costs of funneling athletes to develop elite levels of skill in the squat, deadlift, and bench.

To unpack where these standards come from first series of questions with these standards are:

where do they originate from?

what is the transfer of training to various sports?

what about the joint prerequisites of different athletes in different sports?

Origins

As mentioned, the origin of such standards aren’t overly clear, but seem to stem from empirical data in Olympic and Powerlifting communities, Soviet research, and industry standards (NSCA, ACSM, USAW). Two well respected books in the world of strength training are Supertraining by Mel Siff and The Science and Practice of Strength Training by Vladimir Zatsiorsky. Needless to say both of these authors deserve all the respect for the wealth of knowledge they’ve contributed to the strength training world. It is worth noting that both authors studied Soviet research extensively, and soviet research was based on elite athletes involved in both Powerlifting and Olympic Weightlifting (there was also research done in jumpers, sprinters, throwers, and wrestlers to name a few). The point being, Olympic weightlifting and Powerlifting are specific sports. This is a crucial component well worth chewing on for strength practitioners working with athletes in different sports and non-athletes who fall into the ‘general population’ category of humans. There is no doubt that these sport specific standards from elite athlete have percolated into the minds of many hobbyist strength practitioners pursuing them personally or holding clients to such standards. Why are we holding different athletes, from different sports, with different needs, capacities, and limitations to such standards?

A simple point illustrates the oversight here. Basketball is a relative strength sport, whereas being an NFL lineman would require you to move your bodyweight plus that of another athlete (borrowing the example from FRS® instructor John Quint). Are these the same sports? Should the preparation be the same? I will save athlete limitations and capacities for later. In a sport like basketball, how strong would you need to make that athlete? Where would you put a pin in developing strength and simply maintain adequate levels of strength such that left over training energy that would otherwise be put into “getting stronger” could now be funneled into say, more connective tissue based training for the insults that come from sport specific demands on a foot, ankle, knee, and hip joint?

Transfer of Training

Here is where the argument typically follows that if you get an athlete “stronger”, transfer of training will ensue. However, is that really realistic to set as an expectation? A squat comes in many different forms. Is the consensus that a back squat, zercher, or box squat are going to equally transfer training to the needs of a basketball and football player? There is a key difference between getting an athlete strong enough for their sport, and getting them as strong as possible for their sport. The former leaves space to address fundamental joint and connective tissue training, whereas the latter requires all physiological resources to be put into building an athlete for a vastly different sport (e.g. it doesn’t take a genius to recognize that powerlifting is not basketball).

Different sports have different demands. It is puzzling as to why so many strength standards remain the similar across sports when looking at athletes from various backgrounds. In other words, using powerlifting or olympic lifting standards for athletes that is a basketball or football athlete. A football lineman IS an example of an athlete who HAS to move the bodyweight of another lineman. Here is a good argument for building enough strength for such demands (though a simple example of their bodyweight + the bodyweight of the opposing lineman). But how about a basketball athlete? Or a tennis player? Do they have the same strength demands in their sport?

Here is where yet another typical argument follows, “you can’t go wrong with strong” to quote Dr Andreo Spina, founder and creator of Functional Range Systems. Except that you 100% can. Just walk into your local gym and ask a random sample of athletes how their joints feel day to day when they wake up. Better yet, go to a basketball game and ask those athletes 1) what their training maxes are and 2) what their joints feel like day to day. You’l likely get one of two answers. “I don’t do max lifting because I have a bad back” or “I bench 250lbs but I have really chronic shoulder issues”. Is the problem evident yet? You can’t apply strength training standards, that come from a specific sport, and apply them to different sports. The SAID principle (specific adaptations to imposed demands) states, “the human body adapts specifically to imposed demands). How a football athlete needs to train for the sport of football SHOULD differ from how a basketball athlete trains for the sport of basketball.

Let’s be clear that if an average gen pop person DOES NOT need to adhere to any of the current standards. Realistically, my clients who are moms, tech company CEOs, and teachers are NEVER going to be in a situation where they need to move 375lbs. So why would I waste their time, and risk injury, pursuing such goals? Most of them are going to be moving THEIR BODYWEIGHT, plus, some external load at various points in their life. Do I make my gen pop athletes lift weights? Absolutely, but only enough to stimulate the kind of strength they need for health and longevity. This requires a comprehensive history, in depth assessment, outlining training goals, tissue specific limitations, and the rest. From there, the question of how strong to make your athletes is entirely answerable. There are too many examples of gen pop athletes thinking they need to lift 375lbs, and doing so, at the cost of compounding pre-existing hip and spine dysfunction. Wouldn’t their training energy be better spent building their joint based capacities so they can be better movers while also building enough (not as much as possible) strength as they need?

The elephant in the room. Joint specific prerequisites.

The capacities of each individual athlete varies, not generally, but specifically. A basketball players hips have no responsibility to their strength coach to be generally the same as their teammates, that of a football players, or a yogi. The same goes for gen pop. No two people I have met between teaching seminars with FRS® or working with athletes one on one have ever presented the same two pairs of hips. That is simply because history, injuries, and capacities vary over an individuals lifespan. This means that the interventions are going to be different from person to person. Herein lies the problem with taking a general approach to strength training. The best program in the world doesn’t exist. Even if there was, the best strength program doesn’t make any sense if the joint and connective tissue prerequisites aren’t considered as we are only putting the cart before the horse in continuing to default to such approaches in standard, general approaches to athlete development.

The reason I use the FRS system with all of my clients, athletes, and myself every day is because it solves the scope of considerations one needs to make with any human in front of them. Note the FRS system is not a ‘method’, it isn’t ‘5’ exercises or another approach to exercise programming. It is a necessary shift in perspective, unmet by the standard model (and created really as a response to where standard approaches fall short). This framework provides a systematic thought process to assess joint specific prerequisites, address tissue specific weak points and blindspots, improve neurological control, and develop strength at the joint, connective, and muscular tissue levels.

Specific > General.

The origins of strength training programming stem from studies in a specific sport (Olympic weightlifting and Powerlifting). Most athletes and gen pop are neither of these. The transfer of training isn’t realistically applicable because of the law of specificity (a barbell squat is not dribbling a basketball). To clarify, I am not saying gen pop or professional athletes can’t benefit from being stronger. I am saying that how strong you need to be for your sport or goals is answerable and it is NOT “as strong as possible”. In conjunction with these questions we should be thinking about the transfer of training, the point of diminishing returns with strength training using a powerlifting lens, and where the time, specificity, and priority is for fundamental components of the musculoskeletal system like joints and connective tissues - which are 100% trainable. Improving the standards for athlete care and injury management requires an individual, tissue specific approach. Joint by joint, limitation by limitation, with a refined understanding that training energy is finite. Where and how we ask athletes to spend it matters.

If you’re interested in 1:1 training, or if you’re an FRS® provider and need help connecting the dots, (remember coaches need coaches) visit www.theartofstrong.com

If you’re a fitness professional or manual therapist interested in taking a course with us, visit www.functionalananatomyseminars.com

References

Rippetoe, M. (2007). Starting Strength: Basic Barbell Training. 3rd ed. The Aasgaard Company.

Wendler, J. (2010). 5/3/1: The Simplest and Most Effective Training System for Raw Strength. Jim Wendler.

Simmons, L. (2006). Westside Barbell Book of Methods. Westside Barbell.

Siff, M. (2003). Supertraining. Supertraining Institute.

Zatsiorsky, V. (2006). The Science and Practice of Strength Training. Human Kinetics.

Simplifaster. (2025). "Applying Relative Strength Standards." Retrieved from https://simplifaster.com/articles/applying-relative-strength-standards/

National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA). (2016). Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. 4th ed. Human Kinetics.

American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). (2017). ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 10th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

USA Weightlifting (USAW). (2020). USA Weightlifting Coaching Manual. USA Weightlifting.

Couldn’t agree more. Thanks for all the quality content. Would love to deep dive answering the question objectively for specific sports to give ROM strength targets based on any available data out there for each sport and translate that back to possible programming for a joint or joint at highest risk of injury in that sport if joint function isn’t prioritized. Thanks!